Hotel

by Alfian Sa'at and Marcia Vanderstraaten

W!LD RICE

Singapore International Festival of Arts 2015: Post-Empire

Victoria Theatre, Singapore

The setting for each scene (set at intervals of ten years) is a room in a grand, unnamed Singapore hotel. Over the years, a host of colourful characters arrive and leave but this room itself remains largely unchanged. The hotel staff turn up at the end of each scene and help with the transitions, suggesting a sense of omnipresence in this venerable institution which has stood the test of time, much like our country. These transitions are visual treats in and of themselves, giving us a flavour of each era depicted. In the first half, this manifests itself in a series of different national anthems (British, Japanese, Malaysian and finally Singaporean) that are sung to show the different empires that the country is part of. Other transitions conjure up the mood of each passing decade as we hurtle through history.

And indeed, Hotel is a celebration of Singapore's intensely rich history, both glorious and grim. Yet Alfian and Vanderstraaten do not merely rehash well-worn themes. These are always re-worked and re-contextualised to gain an added potency. The opening scene featuring a British couple honeymooning in 1915 on the day of the mass public execution of mutinous sepoys throws up poignant questions about racism and draws a grim parallel to the Little India riots just two years ago. A 1925 scene concerning the abuse of a Cantonese maid by her wealthy employer evokes the continuing problem of violence against domestic workers.

It's this constant interplay between the present and the past that keeps the play so absorbing. A necklace gifted by a visiting newlywed to a bellboy miraculously resurfaces, eighty years later, as a family heirloom which an Indian lady presents to her Chinese daughter-in-law on the latter's wedding day. In Cloud Atlas-like fashion, both young brides are played by the same actress, suggesting that history itself has come full circle. Two young Malay girls reappear as grandmothers in later scenes, haunted by their brighter past. The husband and wife in the final scene share the same first names (Henry and Margaret) as the couple from the very first scene. While the first pair are foreigners stepping into a world of Singaporeans, the final pair are locals who find themselves surrounded by foreign members of staff. There is both continuity and change.

One of the richest aspects of Hotel is its use of language. This not only reflects the diversity of Singapore's people but the changing empires over time. In the pre-independence scenes, English is seen as a language of power and associated with the authorities. This changes in the later decades when English becomes the dominant lingua franca and grows more malleable and colloquial. Language is both a tool to include (a Chinese and Indian co-worker in an early scene naturally communicate in Malay, the national language) but also a means to exclude (a wedding scene sees a Chinese mother deliberately speak in her mother tongue to alienate her Indian guests). The actors also display an impressive ability to switch languages from one scene to the next. Sharda Harrison, Neo Swee Lin and Lim Kay Siu perform an entire scene in Japanese while Julie Wee dazzles with Malay.

The ensemble cast do a wonderful job in bringing each scene to life. Crowd favourites include a hilarious song-and-dance sequence between actor-filmmaker P Ramlee and an ardent fan (with standout performances by Siti Khalijah and Jo Kukathas) and an over-the-top dream sequence involving dancing penises. Hotel is also one of the rare plays where the actors portray individuals that reflect that own heritage. Julie Wee and Brendon Fernandez both play Eurasian characters while real-life couple Neo Swee Lin and Lim Kay Siu are proudly Peranakan on stage.

Co-directors Ivan Heng and Glen Goei manage the action on stage with incredible flair and there is enough variety to please even the most fussy member of the audience. Comedy is balanced out well with hard-hitting moments of drama and there is a good mix of spectacle and intimacy in the scenes. A evocative opening and closing prologue featuring travellers with suitcases captures the idea of individuals being in a constant state of flux, mere visitors in this ever-evolving world. This idea is brought home in the final scene. A dying man - a stranger in his own country - returns to the room where he spent his wedding night to live out his final days because it is the one space which he feels has not changed. It reminds us that nothing in this world is ever constant; the best we can do as human beings is to reach out for the familiarity of fleeting moments.

The play is however not without its flaws. The surtitles - so crucial in a play as linguistically diverse as this - can sometimes appear quite faint against the wall with its multi-coloured wallpaper projections, making it difficult for audience members to follow entire scenes. A cheeky sequence where the statue of Raffles gets ushered out of the hotel room to signify the end of colonial rule feels rather heavy-handed. The 1965 scene, exploring a fractured relationship between a Malaysian and a Singaporean co-worker, proves a little unwieldy when it introduces two sub-plots about hotel staff dealing with the implications of Singapore's separation from Malaysia that prove far more engrossing than the main story. The 2005 scene, set in the context of a post-9/11 world and featuring a Malaysian Muslim man being rudely interrogated by the police, strikes one as being incongruously harsh in tone.

The Crystalwords score: 5/5

W!LD RICE

Singapore International Festival of Arts 2015: Post-Empire

Victoria Theatre, Singapore

Two playwrights. Two directors. Thirteen actors. Eleven scenes spanning one hundred years of Singapore history. Hotel is not only one of the longest plays in the Singapore theatre canon (spanning some four and a half hours) but also, I daresay, one of our finest pieces of original writing to date and the state-of-the-nation play we so desperately need.

This special commission for the Singapore International Festival of Arts was devised over a period of nine months, involving a healthy workshopping process amongst the team. Characters and scenarios were improvised for each decade, independent research was carried out and the script, jointly written by Resident Playwright Alfian Sa'at and Associate Artist Marcia Vanderstraaten, organically grew out of these discussions. It's the first time W!LD RICE have used this collaborative approach in creating theatre and the proof is in the pudding.

The setting for each scene (set at intervals of ten years) is a room in a grand, unnamed Singapore hotel. Over the years, a host of colourful characters arrive and leave but this room itself remains largely unchanged. The hotel staff turn up at the end of each scene and help with the transitions, suggesting a sense of omnipresence in this venerable institution which has stood the test of time, much like our country. These transitions are visual treats in and of themselves, giving us a flavour of each era depicted. In the first half, this manifests itself in a series of different national anthems (British, Japanese, Malaysian and finally Singaporean) that are sung to show the different empires that the country is part of. Other transitions conjure up the mood of each passing decade as we hurtle through history.

And indeed, Hotel is a celebration of Singapore's intensely rich history, both glorious and grim. Yet Alfian and Vanderstraaten do not merely rehash well-worn themes. These are always re-worked and re-contextualised to gain an added potency. The opening scene featuring a British couple honeymooning in 1915 on the day of the mass public execution of mutinous sepoys throws up poignant questions about racism and draws a grim parallel to the Little India riots just two years ago. A 1925 scene concerning the abuse of a Cantonese maid by her wealthy employer evokes the continuing problem of violence against domestic workers.

It's this constant interplay between the present and the past that keeps the play so absorbing. A necklace gifted by a visiting newlywed to a bellboy miraculously resurfaces, eighty years later, as a family heirloom which an Indian lady presents to her Chinese daughter-in-law on the latter's wedding day. In Cloud Atlas-like fashion, both young brides are played by the same actress, suggesting that history itself has come full circle. Two young Malay girls reappear as grandmothers in later scenes, haunted by their brighter past. The husband and wife in the final scene share the same first names (Henry and Margaret) as the couple from the very first scene. While the first pair are foreigners stepping into a world of Singaporeans, the final pair are locals who find themselves surrounded by foreign members of staff. There is both continuity and change.

|

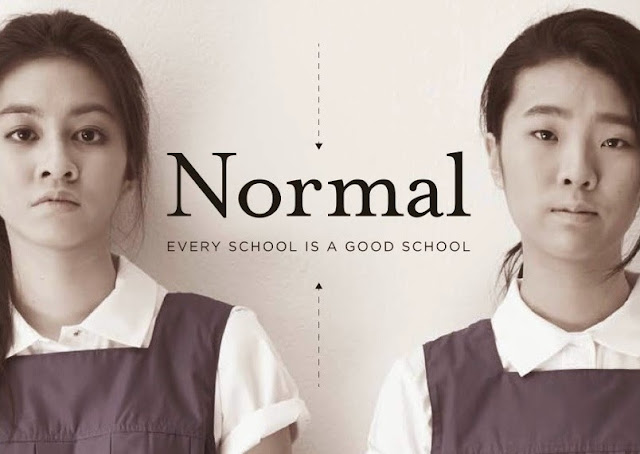

| Photo Credit: Albert Lim KS/W!LD RICE |

One of the richest aspects of Hotel is its use of language. This not only reflects the diversity of Singapore's people but the changing empires over time. In the pre-independence scenes, English is seen as a language of power and associated with the authorities. This changes in the later decades when English becomes the dominant lingua franca and grows more malleable and colloquial. Language is both a tool to include (a Chinese and Indian co-worker in an early scene naturally communicate in Malay, the national language) but also a means to exclude (a wedding scene sees a Chinese mother deliberately speak in her mother tongue to alienate her Indian guests). The actors also display an impressive ability to switch languages from one scene to the next. Sharda Harrison, Neo Swee Lin and Lim Kay Siu perform an entire scene in Japanese while Julie Wee dazzles with Malay.

The ensemble cast do a wonderful job in bringing each scene to life. Crowd favourites include a hilarious song-and-dance sequence between actor-filmmaker P Ramlee and an ardent fan (with standout performances by Siti Khalijah and Jo Kukathas) and an over-the-top dream sequence involving dancing penises. Hotel is also one of the rare plays where the actors portray individuals that reflect that own heritage. Julie Wee and Brendon Fernandez both play Eurasian characters while real-life couple Neo Swee Lin and Lim Kay Siu are proudly Peranakan on stage.

Co-directors Ivan Heng and Glen Goei manage the action on stage with incredible flair and there is enough variety to please even the most fussy member of the audience. Comedy is balanced out well with hard-hitting moments of drama and there is a good mix of spectacle and intimacy in the scenes. A evocative opening and closing prologue featuring travellers with suitcases captures the idea of individuals being in a constant state of flux, mere visitors in this ever-evolving world. This idea is brought home in the final scene. A dying man - a stranger in his own country - returns to the room where he spent his wedding night to live out his final days because it is the one space which he feels has not changed. It reminds us that nothing in this world is ever constant; the best we can do as human beings is to reach out for the familiarity of fleeting moments.

|

| Photo Credit: Albert Lim KS/W!LD RICE |

The play is however not without its flaws. The surtitles - so crucial in a play as linguistically diverse as this - can sometimes appear quite faint against the wall with its multi-coloured wallpaper projections, making it difficult for audience members to follow entire scenes. A cheeky sequence where the statue of Raffles gets ushered out of the hotel room to signify the end of colonial rule feels rather heavy-handed. The 1965 scene, exploring a fractured relationship between a Malaysian and a Singaporean co-worker, proves a little unwieldy when it introduces two sub-plots about hotel staff dealing with the implications of Singapore's separation from Malaysia that prove far more engrossing than the main story. The 2005 scene, set in the context of a post-9/11 world and featuring a Malaysian Muslim man being rudely interrogated by the police, strikes one as being incongruously harsh in tone.

Part 1 of Hotel (covering the years 1915 to 1965) makes a superb, self-contained play that eloquently charts the Singapore story from colonial days to independence. However, one would struggle to view Part 2 (covering 1975 to 2015) as a standalone piece of theatre. The fantastical 1975 scene about a transgender woman coming to terms with her identity proves far too weak an opener for this second part while the full pathos of the 1985 scene, where a Japanese man meets his Singaporean biological mother after four decades apart, can only be fully appreciated if one had seen the earlier scene from Part 1 featuring the mother as a young woman during the war.

Yet these remain but quibbles in a play with such diversity and drive, one that is an intoxicating swirl of languages, cultures and ideologies that have shaped this nation over the course of an entire century. Hotel will immediately go down as a Singapore theatre classic: a play that demands to be seen, read and discussed by both young and old for years to come. I'm glad to hear that a restaging has already been planned for 2016 and look forward to reading the published text one day.

But perhaps most importantly, one should thank the entire team at W!LD RICE for giving Singapore this incredible gift on the jubilee year of her independence: the gift of a voice.

But perhaps most importantly, one should thank the entire team at W!LD RICE for giving Singapore this incredible gift on the jubilee year of her independence: the gift of a voice.

The Crystalwords score: 5/5

Comments

Post a Comment